When I say I work with genetic data, what does that mean? I spend my work hours tapping away on the computer, analyzing animal DNA and writing results into reports or papers. I’ve been a geneticist for several years now, starting from my master’s program (2018-2020) working with birds and now working with whale data 🐋. My experience these past years involved a lot of self-teaching, but I have also received guidance from others, especially from my partner Matt. Between sharing excitement for interesting research and me crying over my overwhelming master’s project, Matt has been my rock that has kept me going in this field of genetics. As a whale geneticist, I am working with really wonderful people doing novel research with goals for wildlife conservation, and I am loving it! It’s challenging, but also very rewarding when the analyses come through. In this post, I will tap the surface about what goes on with processing genetic data through bioinformatics. (See my previous post on DNA extractions for an example of how blood samples are processed).

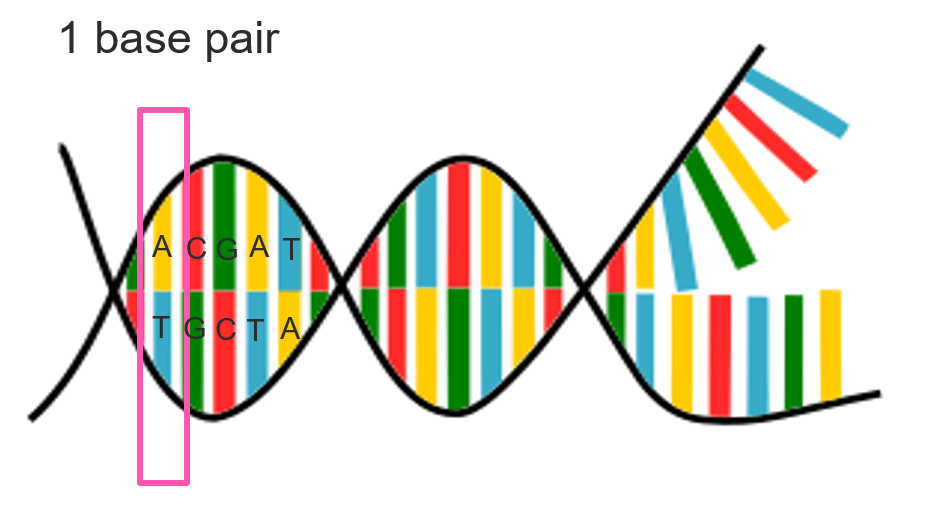

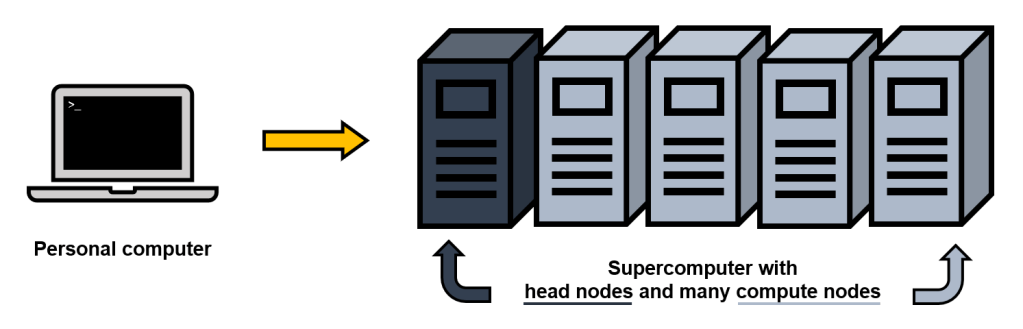

There are different approaches for studying genetics, some methods use mitochondrial DNA (a compact DNA package inherited from mom) or microsatellites (pieces of DNA). Nowadays, genomics (complete set of DNA) is widely used for studying an organism’s biological data. I have only worked with genomic data in my experience, starting with purple martins from my master’s program, so that is where this paragraph is headed. Because DNA is jam-packed with information, datasets derived from DNA is immense in size. For example, a human genome for 23 chromosomes is ~3 billion base pairs (base pairs are the fundamental blocks of DNA, generally composed of nucleotides A,C,G,T). “Billions” might not seem like much when just looking at the word or the zeros (1,000,000,000) but let’s look at another scale: 1 billion seconds is the equivalent to about 32 years 🤯. Quantifying a billion is still just insanely wild to me. So back to genetics– say even in a smaller genome, like a bird genome with ~1 billion base pairs, there is a lot of data to process. Even if other samples in the study are not completed genomes (still covering whole genome but with some missing parts because sequencing is expensive and things are not perfect), if you start working with large quantity of individuals, then the size of the dataset increases immensely. How do we work with these large datasets? Through bioinformatics, we can use specialized computational tools to process and analyze biological data. While we can do bioinformatic work directly on our own personal computer (PC), usually these analyses are done on supercomputers due to storage space and computing power. Supercomputers are essentially amazingly powerful computers, which are built differently than your normal computer at home, and can be accessed through our PC (granted we have authorization). Below is a simplified diagram I made to illustrate this.

There are different “nodes” (the physical device within a network) in a supercomputer. There are head nodes, which are essentially setup or login nodes (where we can move files around, and submit scripts), and many compute nodes, which are where the large analytical processes are completed. An example of a network that has an advanced computing system is Compute Canada. When using these computing clusters (which I access through my PC), I use applications PuTTY for a text-based user interface (command-line) and WinSCP for file transfer between my PC (local) and the supercomputer (remote). Using these two programs, I can organize my data, run scripts, and access results from those scripts.

The storage space on a supercomputer helps keep large files in order. For my master’s project, the raw sequencing files for all my data (just under 100 bird samples) were a whopping 350 gigabytes (GB). My laptop alone has a total storage space of 930 GB, so you can see how if I were to save everything on my laptop space would fill up very quickly. Instead, I would store these data files on a supercomputer that has significantly more space, and where I can run programs to work with the data. It also important to back-up data on external hard drive and/or cloud storage such as Google Drive. Once erased from a supercomputer, it is gone. I will note here though, that usually in the end of some analyses the result files are small and I can transfer these over to my PC to continue working with them in R, a very useful programming tool for statistical analyses and data visualization.

The majority of the time doing bioinformatics is troubleshooting. It can take days or weeks to figure out how to get programs to run, or to explore the appropriate settings for your data. (I’ve even taken days just to figure out the installation process for some programs 🙃). We can run “jobs” on the supercomputer, where we submit a script we put together (a popular way to write scripts is through the handy Notepad++), which is helpful for long tasks that require hours, days, or even weeks, without having to keep your PC on. On a supercomputer (like the Compute Canada computing cluster I mentioned) many people are on it running their scripts, and to allocate computing power for everyone these scripts need to have requested memory and computing time specified. Generally, job scripts with lower memory and shorter run time are given higher priority over ones that need larger memory and longer computing time. This means we might have to wait a while for a long job to start (sometimes hours or days in queue). And how do we know how much memory and time is needed for a program to run? Sometimes there examples online that could be used as guidelines, but often we just need to troubleshoot. For computing time, I’ve overestimated, underestimated, and rarely when I’m lucky I’ve estimated the right time with only a minute to spare. While these job scripts are wonderful to run something overnight, over the week, etc, it also means that when an error occurs, it can take a long time to get it done right. More than 90% of my job scripts end in errors. Sometimes doing test runs on a subset of data first is great for making sure your code runs smoothly before committing to longer timeline, but even still we can run into memory issues or something else. I’ve had scripts run for multiple days, then exit on an error, which I have to fix and then re-try. Again, and again. Until it works! And then move on to the next step to troubleshoot. If something worked without error on the first try, it seems very suspicious 🤔.

So what exactly am I running and what programs do I need to use to analyze my datasets? I don’t have a straight answer for this, because there are various steps involved depending on the specific analysis and there are multiple programs that can accomplish similar things. For example, filtering genetic variants to remove low-quality data can be done with programs GATK, VCFtools, PLINK, to name a few. Each program also requires specific data formats, which may need to be prepared by using other programs. While it can be overwhelming to have many options, it is also handy to have many tools available to use what’s best for our dataset. After processing and filtering genomic data, there are numerous things to investigate! The direction of my work included examining population structure, demographic history, genome-wide association studies, selective sweeps, and more. Bioinformatics is a very powerful application of tools to analyze genetic data since it can be can be applied to all sorts of organisms. I think it’s also super neat how we can use supercomputers remotely through our own fingertips!

-Evelien